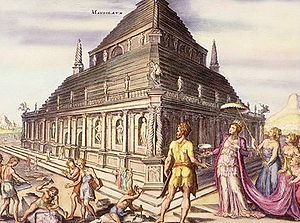

Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus[1] (in Greek, Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ) was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC at Halicarnassus (present Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, a satrap in the Persian Empire, and Artemisia II of Caria, his wife and sister. The structure was designed by the Greek architects Satyros and Pythis.[2][3] It stood approximately 45 m (148 ft) in height, and each of the four sides was adorned with sculptural reliefs created by each one of four Greek sculptors — Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas of Paros and Timotheus.[4] The finished structure was considered to be such an aesthetic triumph that Antipater of Sidon identified it as one of his Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The word mausoleum has since come to be used generically for any grand tomb.

Contents |

Conquest

623 BC, Halicarnassus was the capital of a small regional kingdom in the coast of Asia Minor. In 377 BC the ruler of the region, Hecatomnus of Milas, died and left the control of the kingdom to his son, Mausolus. Hecatomnus, a local satrap under the Persians, took control of several of the neighboring cities and districts. After Artemisia and Mausolus, he had several other daughters and sons: Ada (adopted mother of Alexander the Great), Idrieus and Pixodarus. Mausolus extended its territory as far as the southwest coast of Anatolia. Artemisia and Mausolus ruled from Halicarnassus over the surrounding territory for twenty-four years. Mausolus, although descended from local people, spoke Greek and admired the Greek way of life and government. He founded many cities of Greek design along the coast and encouraged Greek democratic traditions.

Halicarnassus

Mausolus decided to build a new capital; a city as safe from capture as it was magnificent to be seen. He chose the city of Halicarnassus. If Mausolus' ships blocked a small channel, they could keep all enemy warships out. He started to make of Halicarnassus a capital fit for a warrior prince. His workmen deepened the city's harbor and used the dragged sand to make protecting breakwaters in front of the channel. On land they paved streets and squares, and built houses for ordinary citizens. And on one side of the harbor they built a massive fortified palace for Mausolus, positioned to have clear views out to sea and inland to the hills — places from where enemies could attack.

On land, the workmen also built walls and watchtowers, a Greek–style theatre and a temple to Ares — the Greek god of war.

Artemisia and Mausolus spent huge amounts of tax money to embellish the city. They commissioned statues, temples and buildings of gleaming marble. In the center of the city Artemisia planned to place a resting place for her body, and her husband's, after their death. It would be a tomb that would forever show how rich they were.

In 353 BC Mausolus died, leaving Artemisia broken-hearted. It was the custom in Caria for rulers to be siblings; such incestuous marriages kept the power and the wealth in the family. As a tribute to him, she decided to build him the most splendid tomb, a structure so famous that Mausolus's name is now the eponym for all stately tombs, in the word mausoleum. The construction was also so beautiful and unique it became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Soon after construction of the tomb started, Artemisia found herself in a crisis. Rhodes, a Greek island at the Aegean Sea, had been conquered by her and Mausolus. When the Rhodians heard about her husband's death, they rebelled and sent a fleet of ships to capture the city of Halicarnassus. Knowing that the Rhodian fleet was on the way, Artemisia hid her own ships at a secret location at the east end of the city's harbor. After troops from the Rhodian fleet disembarked to attack, Artemisia's fleet made a surprise raid, captured the Rhodian fleet and towed it out to sea. Artemisia put her own soldiers on the invading ships and sailed them back to Rhodes. Fooled into thinking that the returning ships were their own victorious navy, the Rhodians failed to put up a defense and the city was easily captured, quelling the rebellion.

Artemisia lived for only two years after the death of her husband. The urns with their ashes were placed in the yet unfinished tomb. As a form of sacrifice ritual the bodies of a large number of dead animals were placed on the stairs leading to the tomb, then the stairs were filled with stones and rubble, sealing the access. According to the historian Pliny the Elder, the craftsmen decided to stay and finish the work after the death of their patron "considering that it was at once a memorial of his own fame and of the sculptor's art."

Construction of the Mausoleum

Artemisia spared no expense in building the tomb. She sent messengers to Greece to find the most talented artists of the time. These included Scopas, the man who had supervised the rebuilding of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus. The famous sculptors were (in the Vitruvius order) Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas and Timotheus, as well as hundreds of other craftsmen.

The tomb was erected on a hill overlooking the city. The whole structure sat in an enclosed courtyard. At the center of the courtyard was a stone platform on which the tomb sat. A stairway flanked by stone lions led to the top of the platform, which bore along its outer walls many statues of gods and goddess. At each corner, stone warriors mounted on horseback guarded the tomb. At the center of the platform, the marble tomb rose as a square tapering block to one-third of the Mausoleum's 45 m (148 ft) height. This section was covered with bas-reliefs showing action scenes, including the battle of the centaurs with the lapiths and Greeks in combat with the Amazons, a race of warrior women.

On the top of this section of the tomb thirty-six slim columns, ten per side, with each corner sharing one column between two sides; rose for another third of the height. Standing between each column was a statue. Behind the columns was a solid cella-like block that carried the weight of the tomb's massive roof. The roof, which comprised most of the final third of the height, was pyramidal. Perched on the top was a quadriga: four massive horses pulling a chariot in which rode images of Mausolus and Artemisia.

Medieval and modern times

The Mausoleum overlooked the city of Halicarnassus for many years. It was untouched when the city fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BC and still undamaged after attacks by pirates in 62 and 58 BC. It stood above the city's ruins for sixteen centuries. Then a series of earthquakes shattered the columns and sent the bronze chariot crashing to the ground. By 1404 AD only the very base of the Mausoleum was still recognizable.

The Knights of St John of Malta invaded the region and built a massive castle called Bodrum Castle. When they decided to fortify it in 1494, they used the stones of the Mausoleum. In 1522 rumors of a Turkish invasion caused the Crusaders to strengthen the castle at Halicarnassus (which was by then known as Bodrum) and much of the remaining portions of the tomb were broken up and used in the castle walls. Sections of polished marble from the tomb can still be seen there today.

At this time a party of knights entered the base of the monument and discovered the room containing a great coffin. In many histories of the Mausoleum one can find the following story of what happened: The party, deciding it was too late to open it that day, returned the next morning to find the tomb, and any treasure it may have contained, plundered. The bodies of Mausolus and Artemisia were missing too. The Knights claimed that Muslim villagers were responsible for the theft. Today, on the walls of the small museum building next to the site of the Mausoleum we find a different story. Research done by archeologists in the 1960s shows that long before the knights came, grave robbers had dug a tunnel under the grave chamber, stealing its contents. Also the museum states that it is most likely that Mausolus and Artemisia were cremated, so only an urn with their ashes were placed in the grave chamber. This explains why no bodies were found.

Before grinding and burning much of the remaining sculpture of the Mausoleum into lime for plaster, the Knights removed several of the best works and mounted them in the Bodrum castle. There they stayed for three centuries.

In the 19th century a British consul obtained several of the statues from the castle, which now reside in the British Museum. In 1852 the British Museum sent the archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton to search for more remains of the Mausoleum. He had a difficult job. He didn't know the exact location of the tomb, and the cost of buying up all the small parcels of land in the area to look for it would have been astronomical. Instead Newton studied the accounts of ancient writers like Pliny to obtain the approximate size and location of the memorial, then bought a plot of land in the most likely location. Digging down, Newton explored the surrounding area through tunnels he dug under the surrounding plots. He was able to locate some walls, a staircase, and finally three of the corners of the foundation. With this knowledge, Newton was able to determine which plots of land he needed to buy.

Newton then excavated the site and found sections of the reliefs that decorated the wall of the building and portions of the stepped roof. Also discovered was a broken stone chariot wheel some 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in diameter, which came from the sculpture on the Mausoleum's roof. Finally, he found the statues of Mausolus and Artemisia that had stood at the pinnacle of the building. In October 1857 Newton carried blocks of marble from this site by the HMS Supply and landed them in Malta. These blocks were used for the construction of a new dock in Malta for the Royal Navy. Today this dock is known at Dock No. 1 in Cospicua, but the building blocks are hidden from view, submerged in Dockyard Creek in the Grand Harbour.

From 1966 to 1977, the Mausoleum was thoroughly researched by Prof. Kristian Jeppesen of Aarhus University, Denmark. He has produced a six-volume monograph, The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos.

The beauty of the Mausoleum was not only in the structure itself, but in the decorations and statues that adorned the outside at different levels on the podium and the roof: statues of people, lions, horses, and other animals in varying scales. The four Greek sculptors who carved the statues: Bryaxis, Leochares, Scopas and Timotheus were each responsible for one side. Because the statues were of people and animals, the Mausoleum holds a special place in history, as it was not dedicated to the gods of Ancient Greece.

Today, the massive castle of the Knights of Malta still stands in Bodrum, and the polished stone and marble blocks of the Mausoleum can be spotted built into the walls of the structure. At the site of the Mausoleum itself, only the foundation remains, together with a small museum. Some of the surviving sculptures at the British Museum include fragment of statues and many slabs of the frieze showing the battle between the Greeks and the Amazons. There the images of Mausolus and his queen forever watch over the few broken remains of the beautiful tomb she built for him.

Modern buildings based upon the Mausoleum of Maussollos include Grant's Tomb and 26 Broadway in New York City, Los Angeles City Hall, the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, Australia, the spire of St. George's Church, Bloomsbury in London, the Indiana War Memorial (and in turn Chase Tower) in Indianapolis,[5] the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite Southern Jurisdiction's headquarters, the House of the Temple in Washington D.C., the Civil Courts Building in St. Louis, and the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Pittsburgh.[6]

Notes

- ↑ "Mausoleion" meant "[building] dedicated to Mausolus"; thus, Mausoleum of Mausolus is a tautology..

- ↑ Kostof, Spiro (1985). A History of Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-19-503473-2.

- ↑ Gloag, John (1969) [1958]. Guide to Western Architecture (Revised Edition ed.). The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 362.

- ↑ Smith, William (1870). "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, page 744". http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-dgra/0751.html. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ in.gov

- ↑ Christine H. O'Toole (September 20, 2009). "The Long Weekend: Pittsburgh, Three Ways". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2009/09/14/ST2009091402834.html.

Further reading

- Kristian Jeppesen, et al. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, 6 vols.

External links

- [1] - The Tomb of Mausolus (W.R. Lethaby's reconstruction of the Mausoleum, 1908)

- Livius.org: Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

|

|||||